Grammatical, automatic furigana with SQLite and Rust

autoruby: an exercise in text processing.

(Note: There is a follow-up post with some optimizations to this project.)

I started working on a personal project that I’m calling autoruby. Its target user is somewhat niche: the tech-savvy, non-fluent reader of the Japanese language. Therefore, although I will briefly explain the problem the project is trying to solve, don’t be too worried if it isn’t entirely clear: at its core, we’re just storing and looking up data, and the point of this article is not to teach Japanese, but to describe a solution to an interesting problem.

(There’s a decent amount of introductory material to this post that you’re more than welcome to read if you want to get the full context, but if you’re just here for some juicy, marginally “blazingly fast” Rust content, skip down to here.)

The problem

Written Japanese and pronunciation guides

(If you’re already familiar with Japanese and furigana, feel free to skip this section.)

The written Japanese language consists of three writing systems: hiragana, katakana, and kanji. The first two, hiragana and katakana, are syllabaries, meaning that each letter represents a particular sound.1

Hiragana

| Character | Sound |

|---|---|

| あ | a |

| き | ki |

| … | … |

Katakana

| Character | Sound |

|---|---|

| ア | a |

| キ | ki |

| … | … |

Kanji

However, kanji characters (Chinese characters) represent meanings rather than sounds. Although kanji characters typically have one or a few common readings, some words will have a completely unique reading. For example, the most common readings for the character 人 (person) are ひと (“hito”), ジン (“jin”), and ニン (“nin”), as seen in the words:

| Word | Reading | Romanization | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 人々 | ひとびと | hitobito | people |

| 人生 | ジンセイ | jinsei | life |

| 人間 | ニンゲン | ningen | human |

But then, there’s the word 大人 (adult), which is pronounced おとな (“otona”). This is a unique pronunciation, so you just have to know it (or be told it). You can’t figure out this word’s pronunciation from the pronunciations of its constituent kanji.

Also, kanji may change how they’re read based on how they are used (grammatically) in a sentence/phrase:

| Phrase | Meaning | Reading |

|---|---|---|

| 間に合う | to make it (in time for …) | 間 is pronounced ま (“ma”) |

| この間 | recently/the other day | 間 is pronounced あいだ (“aida”) |

A single kanji may be a word all by itself, or part of a larger word:

| Word | Meaning | Reading |

|---|---|---|

| 指 | finger | 指 is pronounced ゆび (“yubi”) |

| 指す | to point (at something) | 指 is pronounced さ (“sa”) |

All of these factors mean that it can sometimes be difficult to discern what the intended reading of a particular word is. Maybe it’s ambiguous, rare, or a word the author constructed. On top of that, if you’re a learner of Japanese, maybe you simply haven’t learned that character yet, so you don’t know how it’s pronounced.

Therefore, sometimes authors will add pronunciation guides to their documents. In Japanese, pronunciation guides are placed above (in horizontal LTR texts) or to the right of (in vertical RTL texts) the words they are describing. The pronunciation guides are called “furigana.” Furigana are typeset using ruby annotations.

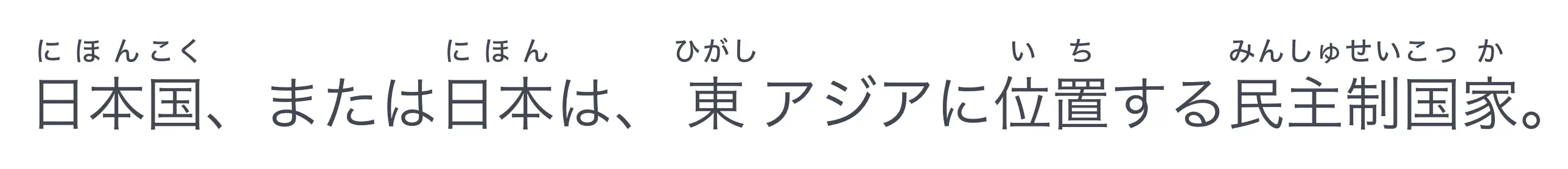

If your browser supports the <ruby> element, the below text should appear with furigana in the correct position:

日本国、または日本は、東アジアに位置する民主制国家。2

Here’s a screenshot if the above example doesn’t render correctly:

See the tiny letters on top of the more complicated Chinese characters? That’s the furigana.

Software support

First of all, not all word processors support adding these ruby annotations. Google Docs, for example, conspicuously lacks any sort of user-friendly support for furigana. Microsoft Word and Apple’s Pages application both support pronunciation guides, but the process of adding them is not automated and is fairly tedious.

For example, here is the process in Pages:

- Select the characters you to which you wish to add furigana.

- Right click → “Phonetic Guide Text…”

- Pages attempts to guess what the intended pronunciation guide is. In my experience, it’s correct around half the time. Thus, you type in the correct pronunciation and press return.

(This is actually better than Microsoft Word’s workflow, which I used throughout undergrad, but I don’t have a copy of Office handy at the moment.)

This process might take 10-15 seconds. The kicker is, you have to do this for every single word, and it gets really tedious really quickly. Not to mention that these annotations are equally as finicky to modify after the fact as they are to create in the first place.

What I wish existed is a feature that would analyze the surrounding text and insert the appropriate reading, automatically, for words simply marked as “please add the furigana to this word.” As far as I can tell, neither of the applications mentioned performs any sort of grammatical contextual analysis to more accurately determine what the reading should be.

The setup

A tool that fulfills my ideal would need to do the following:

- Analyze Japanese text in a grammar-aware manner.

- Identify which words need annotations.

- Generate (or look up) the correct reading for each word.

And since I’m an incorrigible Rust addict, we’re doing this in Rust.

Morphological analysis

In this step, the raw Japanese input string is split up into individual chunks (approximately by word/particle). These chunks might be inflected (to show tense, negativity, …), so they must be uninflected to a form that can be looked up in a dictionary.

For example, upon receiving this input:

神は「光あれ」と言われた。すると光があった。 3

It should uninflect these words:

| Input | Meaning | Inflection | Output (Uninflected) |

|---|---|---|---|

| あれ | to be | imperative | ある |

| 言われた | to say | passive/respectful | 言う |

| あった | to be | past | ある |

Believe it or not, this is the easy part, since a Rust library already exists for this: Lindera is such a library for Japanese. For Japanese text segmentation, it uses MeCab with the IPADIC dictionary.

Difficult word identification

A better solution would probably use some combination of word and kanji frequency lists or a user-defined reader proficiency level to automatically choose which words need furigana, and a user-defined flag to indicate when a word should get a custom reading would be good, too.

For the most basic version of this tool, we could simply blindly apply furigana to every single word that contains a kanji character. Since kanji are pretty easy to detect (just by Unicode code point), this would be a fast-and-easy, “good enough for now” solution.

Of course, we can do a little bit better than that. At the time of writing, the de-facto standard dictionary for open-source Japanese/English language projects is JMdict, and it contains a lot of information, from furigana (which we’ll be using later) to word frequency. Since the average reader is more likely to know how to read more frequently-used words, we’ll assume that a common word is an easy-to-read word. Actually, JMdict provides quite a few different frequency rankings. To reduce cognitive load on the user, autoruby will have two modes:

- Add furigana to every word with kanji characters.

- Add furigana to words with kanji characters that are determined to not be common.

Furigana acquisition

Now that we know for which words we must generate readings, and what the uninflected forms of those words are, we can simply look them up in a furigana dictionary.4 The furigana data from JMdict have been extracted as part of the JmdictFurigana project on GitHub.

Great! So we can just use these files, right?

Not exactly.

Part of the Rust ethos is that everything has to be blazingly fast™, and unfortunately, opening and scanning a multi-megabyte text file—or worse: an even larger JSON file—every time we want to look up a word isn’t particularly speedy.

Whatever shall we do?

The speedy

Here’s the plan: we’ll parse the data out of the text file and insert it into an SQLite database, which can be queried faster than a text file can be scanned.

Parsing the text file

Even though this is a step we really only have to do once (or, only as often as the source dictionary is updated), we’re still going to try to make it fast.

A brief introduction to nom

nom is a parsing library for Rust. Nom parsers are just functions that match a certain signature, and they’re made by composing smaller parsers together using combinator functions. In many applications, a nom parser can fill the same role as a regular expression, but it’s much more flexible and testable (not to mention faster).

Listing: Simple parser, substring extraction

use nom::{

bytes::complete::{tag, take_while},

multi::separated_list0,

IResult,

};

pub fn dumb_csv(input: &str) -> IResult<&str, Vec<&str>> {

separated_list0(tag(","), take_while(|c| c != ','))(input)

}

assert_eq!(

dumb_csv("abc,def,123,,!"),

Ok(("", vec!["abc", "def", "123", "", "!"])),

);Nom parsers can return more than just bits and pieces of the target string (like a regex does): it can parse out any type from its input. This makes them quite nice to compose.

Listing: Parser composition

use std::num::ParseIntError;

use nom::{

bytes::complete::take_until1,

character::complete::{char, digit1},

combinator::{map, map_res, opt},

sequence::{preceded, separated_pair, tuple},

IResult,

};

type InclusiveRange = (u8, u8);

pub fn range(input: &str) -> IResult<&str, InclusiveRange> {

map_res(

tuple((digit1, opt(preceded(char('-'), digit1)))),

|(start, end): (&str, Option<&str>)| {

let start: u8 = start.parse()?;

let end = if let Some(end) = end {

end.parse()?

} else {

start

};

Ok::<_, ParseIntError>((start, end))

},

)(input)

}

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq)]

struct AnnotatedRange<'a> {

name: &'a str,

range: InclusiveRange,

}

fn annotated_range(input: &str) -> IResult<&str, AnnotatedRange> {

map(

separated_pair(take_until1(":"), char(':'), range),

|(name, range)| AnnotatedRange { name, range },

)(input)

}

assert_eq!(

annotated_range("key:1"),

Ok((

"",

AnnotatedRange {

name: "key",

range: (1, 1)

}

))

);

assert_eq!(

annotated_range("peele:0-4"),

Ok((

"",

AnnotatedRange {

name: "peele",

range: (0, 4)

}

))

);Our data

Let’s take a look at the contents we’re trying to parse.

指|ゆび|0:ゆび

間に合う|まにあう|0:ま;2:あ

大人|おとな|0-1:おとなEach line of the text looks like this:

- A word with kanji.

- A vertical bar

|. - The complete pronunciation of the word.

- A vertical bar

|. - A semicolon

;-separated list of:- A range, in the form of:

- A single number, indicating an inclusive lower bound and inclusive upper bound.

- A single number, indicating an inclusive lower bound.

- A dash

-. - A single number, indicating an inclusive upper bound.

- A colon

:. - A hiragana string: the pronunciation of the [lower bound, upper bound] substring of the word with kanji.

- A range, in the form of:

Luckily, it is not difficult to write a parser for this pattern. The most complex bit is the numerical range parsing, which has already been shown in the second code listing.

Inserting into a database

Now, the naïve approach is to read all of the data from the text file into some intermediate data structure, and then individually insert each record in the database. However, this is not a solution that scales well with input size, since we’ll have to wait for the database engine to finish executing every insert statement before we can send it another one. (We’re just using a simple SQLite setup here.)

Listing: Slow insertion algorithm (pseudocode)

text_file = read_text_file(dictionary_file_path)

for line in text_file.lines():

result = parse(line)

insert_into_database(result)Instead, we’ll stream in the contents of the input file, reading it line-by-line. This is the kind of thing that std::io::BufReader was built for. As the lines are streaming in, we’ll build up an SQL transaction of insert statements. Individual insert statements take too long to execute, so we’ll batch them in groups of 1000 inserts per transaction.

Listing: Better insertion algorithm (pseudocode)

file_buffer = buffer_lines(dictionary_file_path)

index = 0

begin_database_transaction()

while line = file_buffer.next_line():

if index != 0 and index % 1000 == 0:

commit_database_transaction()

begin_database_transaction()

insert_into_database(parse(line))

index = index + 1

commit_database_transaction()Finding the correct readings

Our work is far from over. We can’t just go looking up words in our database and applying the readings willy-nilly!

Our morphological analyzer has a bit of an issue: sometimes it can be a bit too aggressive with tokenizing the input. Here’s an example of what I mean. If we give the tokenizer "方程式" (“ほうていしき” / “houteishiki” / equation) as input, it correctly returns a single token ["方程式"], which we can then look up in our dictionary. However, if we give it "全単射" (“ぜんたんしゃ” / “zentansha” / bijection), it divides it up into its constituent characters, returning each as a separate token: ["全", "単", "射"].

This is a problem because, as discussed previously, the way that kanji characters are combined affects how they are pronounced, so the tokenizer occasionally giving us back individual characters as tokens somewhat hampers our ability to look them up in the furigana dictionary.

I don’t intend to write my own morphological analyzer, as that is way beyond my realm of expertise. Instead, we’ll make do with what we have.

Here’s the idea: buffer consecutive kanji tokens until their concatenation no longer appears as a prefix of any of the entries in our furigana dictionary, then find the longest concatenation of the buffered tokens that is a complete entry in the dictionary. Here’s the actual implementation of this algorithm at the time of writing. (I’ll be honest: this is the closest I’ve come to writing manual pointer arithmetic in Rust.)

The result

I also wrote a simple CLI that makes the tool a little easier to use. Below are the results of processing an arbitrary book from Project Gutenberg. The test data is 100,845 bytes.

time autoruby annotate in.txt out.md --mode markdown

real 20m31.788s

user 0m0.015s

sys 0m0.062sWell, that’s disappointing.

Actually, it’s just the database thrashing around. If we implement some basic memoization, the speed-up is tremendous:

time autoruby annotate in.txt out.md --mode markdown

real 1m53.411s

user 0m0.000s

sys 0m0.000sThat’s only about 889 bytes per second, which still isn’t great, but at least it’s usable. (Update: See the follow-up post for a significant optimization.)

The future

I’m trying to read more e-books in Japanese, so I think this tool could come in handy. Therefore, adding support for EPUB files is on the agenda. (Right now, only extremely basic text-based formats are supported.) It would also be neat to add an interactive CLI, so the user could manually select which readings to apply where and when. Finally, the long-shot is to make a browser extension that integrates with Google Docs and finally makes it support furigana.

This is also a highly-parallelizable task—so long as we split up the text at known sentence separators, there should be no effect on the generated readings, so this should be a fairly easy application to make multithreaded.

Until then, this was a really fun project, and I’m planning to continue working on it in my spare time going forward.

If you haven’t already, I’d appreciate it if you’d check out the project, maybe try it out, and give it a star?

Technically, I think they’re not actually letters, but graphemes (or just characters, I guess), and there isn’t quite a strict 1:1 correspondence between grapheme and mora (sound), but it doesn’t really matter for our purposes. (Hopefully this satisfies the pedants. Then again, since I’m not a linguist, probably not. Oh, well.) ↩︎

Source: the first sentence of the Japanese Wikipedia article on Japan. ↩︎

Approximate translation: “God said, ‘Light, be! (exist!)’ And then, light was (existed).” Genesis 1:3, 口語訳 ↩︎

The solution I’m proposing assumes:

- Kanji do not vary across inflections of a word.

- Inflections only change the end of a word.

These are by-and-large true, but I’m not sure whether they are always true. ↩︎

Jacob Lindahl is a graduate student at the Tokyo Institute of Technology.